- Home

- Sarah Pinborough

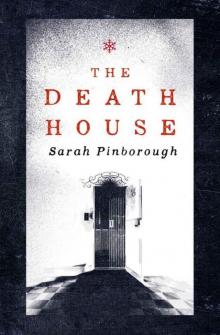

The Death House

The Death House Read online

Dedication

For Johannes,

My partner in crime and wine.

Much love.

THE

DEATH

HOUSE

Sarah Pinborough

GOLLANCZ

LONDON

Contents

Dedication

Title Page

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Acknowledgements

Also by Sarah Pinborough from Gollancz:

Copyright

‘Be happy for this moment. This moment is your life’

Omar Khayyám

One

‘They say it makes your eyes bleed. Almost pop out of your head and then bleed.’

‘Who says?’

‘People. I just heard it.’

‘You made it up.’

‘No, I didn’t,’ Will says. ‘Why would I make that up? I heard it somewhere. You go mad first and then your eyes bleed. I think maybe your whole skin bleeds.’

‘That is such a heap of shit.’

‘Shut up and go to sleep.’ I roll over. The rough blanket scratches me on the outside and my irritation at Will’s overactive imagination scratches me from the inside. I let out a hot breath against the wool. My irritation is irritating me. It comes fast these days, flares from the ball of a black sun that’s been growing quietly in the pit of my stomach. The two boys fall satisfyingly silent. I’m the eldest. I’m the top dog, the boss, the daddy. Of Dorm 4, at least. My word goes.

I yank the starched sheet up until it covers the edge of the old blanket. The dorm isn’t cold so much as cool – the kind of chill ingrained in the bricks and mortar of centuries-old buildings, a ghostly, melancholy chill of things that once-were, now part-lost. We suit the house, I think, and that makes the ball contract in my gut. I shiver and pull my legs up under my chin. My bladder twinges. Great.

‘I can’t sleep,’ Will says plaintively. ‘Not with that going on.’ He yawns then and I can see him in the gloom, sitting up cross-legged on his bed, fiddling with the metal bars at the foot of it. He’s the youngest in our room, and is small for his age. He acts younger, too.

The constant whispering comes from the bed opposite Will’s on the other side of the room. The cuckoo in our nest, Ashley, is on his knees beside it, praying. He does this every night at lights-out. Religiously.

‘I don’t think God is listening,’ I mutter. ‘You know, given the situation.’

‘God’s always listening.’ The prim voice floats in the frigid air – a stretched reed with a breeze cutting across it. ‘He’s everywhere.’

My bladder twitches again and I give in and push back the covers. The floorboards are cold – fuck knows how Ashley’s knees must feel – but I ignore my slippers. I’m not a granddad.

‘Then your praying makes no sense,’ Louis says, matter-of-fact. His bed is closest to the door and he’s staring up at the ceiling, his hair here and there and everywhere. He still gesticulates as he speaks, even though he’s lying down. ‘Because if your God is everywhere then he’s also inside you and therefore you could speak to him from the quiet privacy of your own mind and talk all night if you wanted without making a sound and he would still hear you. Of course, there is absolutely no scientific proof that any form of deity exists, or that we are more than a collection of cells and water, so your God is just a figment of someone’s imagination that you’ve bought into. Basically, you’re wasting your time.’

The whispering gets louder.

‘Maybe he’s having a wank under the bed and trying to cover the noise,’ I say as I reach the door. ‘Fwap fwap fwap.’ I grin as I make the hand gesture.

Louis snorts a laugh.

Will giggles.

My irritation lifts. I like Will and Louis. I wish I didn’t, but I can’t help it. I glance back as I close the door. They look small in the large room. There are too many beds for just the four of us – six against each wall. It’s like everyone else has gone home and somehow we were forgotten. The door clicks shut and I creep along the corridor. It’s a long way to the bathroom and even though I have bigger things to frighten me than the shadows and emptiness of the tired manor house, I still move quickly. The last rounds haven’t been done yet.

I hurry down the wide wooden stairs, clinging to the bannister in the dark as if it were the railing on a ship wearily cutting through the night ocean. The whole house is silent apart from the gentle creaks and moans of the old building itself. I think of the others sleeping in the dorms spread throughout the draughty wings, and the nurses and teachers in their quarters, and then my mind can’t help but imagine the top floor. The one where only the lift goes. Where the kids who get sick disappear to in the night, efficiently removed while the house sleeps. Swallowed by the lift and taken to the sanatorium. We don’t talk about the sanatorium. Not any more. No one ever leaves the house, and no one ever comes back from the sanatorium. We all know that. Just like we know we’ll each make a trip there. One day I’ll be the kid who vanishes in the night.

I pee without closing the door or turning on the light, enjoying the relief even though the liquid stream on ceramic is loud. I don’t flush – Mum’s rule of no flushing at night still sticks – and then I yawn into the mirror without washing my hands. That rule has changed. Germs are not our biggest problem here. Not that, to be honest, I ever remembered much before anyway.

They say it makes your eyes bleed.

I lean in closer and stare at my eyes. They’re normally bright blue but look drowned grey in the grimy night. I pull down one lower lid and can make out the streaks of tiny veins running away to my insides. No blood there, though. It probably isn’t even true. Just Will’s stupid imagination making shit up. I’m fine. We’re all fine. For now.

‘You should be in bed.’

The voice is soft but it makes me jump. Matron stands in the corridor by the window, the moonlight through the glass making her white uniform shine bright. Her bland face is barely visible.

‘Aren’t you tired?’

‘I needed to pee.’

‘Wash your hands and go back to bed.’

I blast cold water onto my palms and then scurry past her, taking the stairs two at a time. It’s the most she’s said to me since I arrived here. I don’t want her to speak to me. I don’t want her to notice me at all, as if somehow that will make a difference.

‘Matron’s coming,’ I whisper, back in my own room.

‘They’re asleep,’ Louis says. The words blur together. I’m not surprised. It’s about the right time.

‘I don’t understand why they give us vitamins before bed,’ Louis slurs. ‘I don’t understand why they give us vitamins at all.’

I half-smile at this from under my rough blankets and too-crisp sheets. Louis – with his six A levels by the age of thirteen, and who’d been racing through university stupidly early before this stopped him – might be some sort of genius, but just like the others, he’s missed the obvious. I don’t point it out. They’re not vitamins; they’re sleeping

pills. Matron and the nurses like the house silent at night.

I wait, tense, for another ten minutes or so before I hear the door handle turn and the soft shuffle of soles as she checks each bed. The last round before morning. Only after she’s gone do I open my eyes and breathe easily.

It was a Friday when they came. It was hot, hotter than normal, and he’d taken his time on the way back from school. He’d bought a Coke from the shop on the corner but the fridge wasn’t working so it was warm and sticky. He drank it anyway, belching loudly after draining it and kicking the can across the street. His mind was drifting through the landscape of the day. Mr Settle droning on about the continuing global climate instability as they all baked and dozed, bored in the classroom. The History essay he owed. The fight with Billy. That was going to come back on him at some point. He didn’t even know why he’d started it other than Julie McKendrick had been watching, and it felt like Julie had been watching him for a few days now, even though he couldn’t quite believe it. Tomorrow night was the party. Tomorrow night, everything could change.

Julie McKendrick was always there in some part of his brain. It was too hot to work. Too hot for school. But it wasn’t too hot to think about Julie McKendrick and the fact that she might actually like him. He was so lost in his own world he didn’t notice how quiet the street was, how all the little kids were inside, not sitting out on the pavements or racing around on their bikes as usual. Billy and the essay had faded and he was mainly wondering if what he felt for Julie really was love or just that she was the fittest girl in the school and he might actually get to kiss her. Maybe even put his hands inside her bra. Just thinking about it made his mouth dry and his heart race. He wondered how it would feel. He wondered if he’d actually find out the next day at the party. Even when he saw the van outside his house, where his dad’s car would be parked later when he got home from work, he still didn’t put two and two together. Not until he heard his mum crying. By then it was too late. And it was too hot to run.

Two

‘My money’s on one of the twins,’ Louis says, and glances at me. ‘You still taking bets, Toby?’

We’re at breakfast, the gong having summoned us down to the wood-panelled space that might once have been an oversized drawing room but is now our dining room. The ornate stone fireplace remains unlit and the only evidence of a previous existence is a tired purple velvet chaise longue pushed up against a wall, and brighter patches on the faded yellow paint where pictures must once have hung. The sun breaks momentarily through the gathering clouds outside and light streams through the vast windows, sending dust-motes dancing curious in the air. The warmth feels good on my face and as I finish my tea, I wonder if maybe Matron and the nurses put something in our breakfast drinks, too, like I heard they used to give men in prison to stop them wanting to fuck or fight.

Louis is trying to eat a fried-egg sandwich made with toast that’s not quite done enough and an egg that’s too runny. Most of it’s going down his T-shirt but he doesn’t seem to care. We’re on a table of our own – our table ever since we arrived. New habits form quickly. There are sixteen tables but only eight are used, one for each of the occupied dorms. We don’t talk to the boys from the other dorms much any more, even though there’s only twenty-five of us left. The girls, Harriet and Eleanor, sit at a table at the back. I’m not sure how old they are, but Eleanor’s still young and Harriet might be older but there’s nothing hot about her. She’s bookish and dumpy and her mouth is nearly always turned down in an unpleasant pout. They have always excluded themselves, and mainly I forget they’re even here.

‘Yep,’ I say. ‘Which one?’

‘Either. I can’t tell them apart. The one who’s trying not to look like he’s sniffing. Is that Ellory or Joe? Whichever, he’s been getting sick and trying to hide it for days.’

The twins are in Dorm 7. Dorm 7, like our own, is still complete. It’s become a matter of unspoken rivalry between us – which dorm will keep a clean survival sheet the longest. Of all the dorms, only Dorm 7 really counts to me. I stare at the table opposite and realise Louis is right. One of the two identical lanky, spotty boys sneakily wipes his nose with the back of his hand. He doesn’t reach for a tissue even though there are paper napkins on the tables. I watch him. It’s really hard to tell. The symptoms can be so different.

‘I’ll take your bet. Two washing-up duties?’

‘Done.’ Louis smiles. ‘I call double or quits. If he goes, the other one goes next.’

‘Why?’ Will sits down with a second bowl of cereal. Will may be tiny but he eats more than anyone I’ve ever known. ‘Cos they know each other?’

‘No, because of science. They’re identical. When it goes in one of them, it’s logical it’ll go in the other soon after. It’s genetic, after all.’

‘Oh,’ Will says. ‘Right.’

‘But that reminds me.’ Louis gets up, egg still dripping from his chin, and before I realise what he’s doing, he’s over at the Dorm 7 table, smiling at Jake.

‘Oh, shit,’ I mutter.

‘Jake,’ Louis starts, ‘I was just wondering if you could help me with something. I’m doing a kind of study of where we’ve all come from and roughly how long it took us to travel here. Firstly it was to find out where exactly we are, but we’ve sort of figured that out now, so I . . .’

‘Oh, this isn’t going to end well,’ Will says, peering over his glasses.

I groan inside. Louis and his stupid information-gathering. No one in the house comes from the same part of the country. We know that. So why does Louis need to know the details? What is it with him and his precision in everything? Over the past week, Louis has become obsessed with trying to collate as much data on the inmates, as he calls us, as he can. This in the main has not gone well. For a start, he’s failed to factor in that people lie. I’ve lied. I’m sure the rest have, too. No one wants to talk about their private history from before anymore and definitely not to someone from another dorm. The nervous friendliness we’d shared at the start is gone. The dorms have become packs and we stay within our own.

‘What the fuck has it got to do with you?’ Jake slowly gets to his feet. He’s speaking quietly – there are nurses by the food station – but the threat is palpable in the air. Cutlery goes down. Heads turn.

‘I thought it would be interesting to—’ Louis, the genius, the prodigy, is oblivious to the tension.

‘Why don’t you just fuck off?’

Jake’s the same age as me, but the stories about him spread on day one, in nods and whispers. He’s been in reform school. He’s stolen cars. I don’t believe a lot of the wild tales of before that I’ve heard in the house, but Jake is different. Jake’s knuckles are scarred and when we first arrived, the back of his head had a gang symbol shaved into it. If you look closely you can still see the shape of it in the new hair. I have no intention of messing with Jake. Jake is no Billy in Year 13.

‘Is Jake going to punch him?’ Will looks at me and, worse, so does Ashley. I’ve got no choice, not if I want to keep whatever respect they have for me.

‘I’ll talk to him.’ If there is some kind of drug in the tea, I’m not feeling it now. My nerves jangle as I walk over to them. Not for what might happen now – the nurses don’t tend to interfere, although I doubt they’ll stand idly by in a fight – but for what might happen later. I never got my beating from Billy. Maybe I’ll get it from Jake instead.

‘Sorry, Jake,’ I say, trying to sound casual. ‘Louis wasn’t thinking.’ I look at the wild-haired boy between us. ‘Go and wipe that egg of your face. You look like a dick.’

‘He looks like he’s been sucking a dick,’ Jake says. His table-mates snigger. They’re gazing up at Jake like he’s a god.

I force a smile.

‘Yeah, I guess he does.’ The worst thing is, now I look at Louis, Jake’s right. A strand of not-quite-cooked-enough egg white is gl

ued to Louis’ chin.

Louis crumples a little, looking hurt, and wipes his mouth. ‘It’s egg,’ he says.

‘Just shut up and sit down, Louis,’ I snarl at him, and Louis, shaken by my tone, drops his head and shuffles back to where Will and Ashley are waiting, finally aware that all the eyes in the room are on him. I look at Jake, not sure where to take this next. ‘Like I said, sorry.’ I turn and walk away.

‘Fucking retards,’ Jake says to my back.

Not retards, Jake, fucking Defectives. We’re all Defectives here.

I don’t say it, though. I just sit down and sip my tea and hope that’s it done. Nobody speaks as we watch Dorm 7 gather up their plates – the youngest, Daniel, a chubby boy of about eleven, clears Jake’s away – and then head out in a line behind their leader, each of them sneering as they go by, as if they think they could all take me on, not just Jake. I ignore them. Only when they’ve gone does Louis look up.

‘You didn’t have to agree with him.’ He’s smarting.

‘Yes he did,’ Ashley says. He’s nibbling a piece of carefully buttered toast. ‘Just because you’re clever, you think you know everything. You don’t. Sometimes you’re plain stupid.’ He sounds smug, no doubt still annoyed with Louis for taking the piss out of his praying last night.

‘Let’s just forget about it.’ I want breakfast over. I wish I could be friends with Jake – not that I like him, but at least we’re the same age. If we were friends I wouldn’t feel as if I’m such a fucking nanny so much of the time.

‘Maybe we’ll get letters today,’ Will says. ‘They said our parents could write to us. They must have written by now. We’ve been here weeks. Maybe they’ll even be able to visit.’

‘Do you still want to learn to play chess?’ Louis says. ‘I’ll teach you, if you like.’

Will smiles, the letters momentarily forgotten. I might be the boss of the dorm, but Will is most fascinated by Louis, and although their minds are miles apart, it’s clear Louis likes Will, too. I wonder what Louis’ life was like before this – all that brilliance but always several years younger than his classmates. No real friends. Always treated like a bit of a freak. I suspect Louis mentioned the chess on purpose to distract Will. There weren’t going to be any letters, and definitely no visits. That had all been clear on my mother’s face as she screamed my name when they put me in the van. This way no one has to know when it happens. It’s cleaner.

Behind Her Eyes

Behind Her Eyes The Chosen Seed: The Dog-Faced Gods Book Three

The Chosen Seed: The Dog-Faced Gods Book Three Dead to Her

Dead to Her Cross Her Heart: A Novel

Cross Her Heart: A Novel Cross Her Heart

Cross Her Heart Into The Silence

Into The Silence Breeding Ground

Breeding Ground The Death House

The Death House A Matter Of Blood (The Dog-Faced Gods Trilogy)

A Matter Of Blood (The Dog-Faced Gods Trilogy) The Language of Dying

The Language of Dying Mayhem

Mayhem Murder

Murder Torchwood_Long Time Dead

Torchwood_Long Time Dead Beauty

Beauty Charm

Charm 13 Minutes-9780575097407

13 Minutes-9780575097407 The Chosen Seed: The Dog-Faced Gods Book Three (DOG-FACED GODS TRILOGY)

The Chosen Seed: The Dog-Faced Gods Book Three (DOG-FACED GODS TRILOGY) The Shadow of the Soul: The Dog-Faced Gods Book Two

The Shadow of the Soul: The Dog-Faced Gods Book Two Into the Silence t-10

Into the Silence t-10